Who knows what you might overhear in a coffee shop?

A crime short story I wrote called ‘The Disappeared’ has been published at East of the Web.

It’s centred on an overheard conversation at an M6 services.

Short stories, poems, journalism

Who knows what you might overhear in a coffee shop?

A crime short story I wrote called ‘The Disappeared’ has been published at East of the Web.

It’s centred on an overheard conversation at an M6 services.

If you have a few seconds free, I’d really appreciate your opinion…..

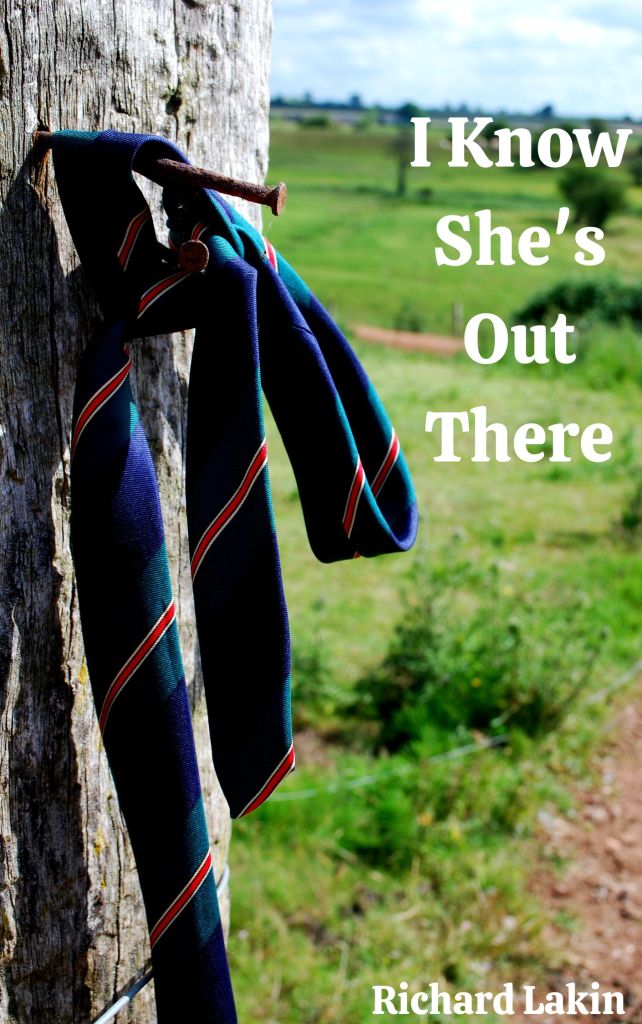

I’ve written a book which, subject to any late changes, I’m going to self publish in the coming weeks.

It’s a suspense/thriller novel of around 95,000 words called ‘I Know She’s Out There.’

I’m preparing the cover and tidying/editing the text at the moment.

To assist I’ve included the elevator pitch below:

After her release from psychiatric care Chrissy Clews is quietly rebuilding her life working at a motorway service station when her former teacher walks in and tries to discreetly buy a porn magazine. He doesn’t recognise her, but when he drops his wallet she hides it and can’t resist looking inside. She’s shocked to find a tatty passport photo of Laura Duggan, a school friend who went missing 30 years ago and was never seen again. She decides to investigate…

I’ve taken some images and mocked up covers. Obviously, I’m an amateur at this kind of thing (very much Sunday pub league), but please let me know if you have a preferred option, or indeed, if another approach is required.

When I publish I’d be delighted if anyone wishes to have a copy to review.

Thanks for your time.

I post this hoping it’s of interest to readers who otherwise will likely not hear of it (reporting in the media has been mostly limited to the Midlands). I’m privileged to have reported on this fascinating case. It’s an enduring mystery.

7.30pm. 27 March 1971.

Precisely 50 years ago tonight. A man is walking his dog beside the River Trent in Burton, Staffordshire when he sees what he thinks is a small disc in the soil. On closer inspection it’s a piece of bone. A man’s skull.

A man has been buried, near naked, in a shallow grave. A murder investigation begins that is still open to this day.

Unsolved murders are very rare and Staffordshire has only a few. Most of the time the victim is known and following their habits and movements leads detectives to their killer.

Unfortunately detectives have never been able to ID this man. No one ever came forward to identify him or report him missing.

His face (pictured below) has been reconstructed and samples of DNA taken as well as exhaustive enquiries into his wedding ring, socks and dentures. There have been possibilities he would be identified including a recent DNA test of relatives of a Welshman missing since 1970.

Alas, there was no link. Yesterday, as the 50th anniversary approached, the senior investigating officer, DCI Dan Ison, made an appeal on Crimewatch.

Known locally and affectionately as ‘Fred’ there is still the hope someone out there knows something, although this dims with time.

’71 was the year of decimalisation, T-Rex were chart topping with Hot Love and Get Carter was on at the cinema.

Such a long time ago. But if the killer can’t be brought to justice perhaps ‘Fred’s ‘ identity can be given back to him…

Full story here Burton murder

My notes on policing the underground have been published in Moxy magazine here..

https://moxymagazine.org/memoir-one-under/

Never a dull moment!

Emma had begged and pleaded and left little sticky notes on the cooker hood and pinned to the cork board above the sink. She’d left catalogues open at the right page on the kitchen table and printouts folded and stuffed in Michelle’s handbag or the dash in the car. No means no, Michelle had said, determined to make a stand. You’re thirteen for God’s sake. Emma had roped her Auntie Julia in, but Julia would agree with anything once she’d cracked open the Merlot.

Michelle went through it all in her head again. All that stuff she’d read in the papers about stalkers and weirdos and stuff happened to other people, didn’t it? Emma showed her mum the local free-sheet. She pointed to an article from the police – WE’RE WATCHING YOU – saying they were online and working hard to combat cyber-crime and grooming. Michelle felt herself wavering, blowing the surface of her tea while she bought time to consider. Emma was a bright girl and you couldn’t watch them all the time, could you? You do your best for them and you send them out into the world, Gary said, as if he’d know. He’d hit the road before Emma had left nursery.

Emma was relentless in wearing her down. All the others have got one. I’m always the one who sticks out, aren’t I? Michelle folded her arms, said her decision was final. End of, she said. But a little voice, like an angel perched on her shoulder, kept telling her: this was you once, Michelle Harvey. You didn’t want to be the odd one out either. She tried not to think of the crepe pumps she’d been forced to wear for PE and the little cord bag she had to carry with her name stitched into the side in shiny gold thread when all the other girls had the latest sports bags. She’d sucked up all that embarrassment, all that shame and here she was passing it on.

‘You’ve got a phone,’ she tried. ‘I don’t see the problem.’

Emma curled her lip. ‘Oh, big deal.’

Michelle took Emma’s hands in hers, but they were stiff and cold. She was wearing perfume, one of her own she’d been bought for Christmas though, no longer a stolen snatch of Michelle’s Marc Jacobs. She didn’t know whether to feel glad or offended about that, but her girl was becoming a woman. ‘Love you, you know.’ Emma muttered that she knew and slumped on the settee, tucking her feet beneath the cushions and ending the conversation.

‘It’s just because I care about you, that’s all.’ She might have added that she knew what men were like, but that would only bring a scoff from Emma. ‘I’m just making sure you stay safe.’

‘Dad says it’s alright.’

‘And he’s concerned about your welfare now, is he?’ Michelle had been separated from Gary for three years. He’d spent two of them at Her Majesty’s pleasure. Gary spared them no time, sent them no money. His sometime role as a parent was agreeing with whatever his daughter wanted and forcing Michelle into the unwanted and thankless role of bad cop.

‘At least he gives me space.’

Yes, twenty-three miles of it, Michelle almost said. ‘You get a lot more freedom than I ever did, young lady.’ Young lady was a borrowed phrase, one of her mother’s. Michelle caught sight of herself in the wardrobe mirror, pale and blotchy and crowbarred into her size 14 jeans, with knitted brows and tired hair that was dull and greasy. Christ, she was becoming her mother. ‘I’m sorry, love,’ she said. Funny that it was the image of her mother – what she was becoming or might become – that broke her in the end. ‘But there’s got to be some ground rules.’ She hated herself, knowing she’d lost already.

Three days later a package arrived and Emma snatched at it, tearing the tablet from the bubble wrap. Michelle was fumbling through the packaging, looking for one of those tiny instruction books in seventeen languages when she noticed Emma was halfway to setting it up, her fingertips gliding across the screen. This was her first tablet, but she didn’t need lessons. Michelle pursed her lips, tried not to think what she might have got up to on Beth’s and Hannah’s already. Emma sprawled out on the settee and took a snap of herself and shared it, squealing when the reply came back from Bethany.

You joined the 21st century at last xx

Emma sprang from the cushions, threw her arms around her mother, hugging her so tight that Michelle’s mohair sweater tickled her cheek. ‘Thanks mum, you’re the best.’

‘Yeah, I have some uses.’

Michelle made them tea, hovering in the hallway while the kettle came to the boil and messages pinged back and forth from Emma’s tablet. Each time a message popped up a little bell rang. Did she have so many friends to talk to? Emma sensed her mother’s presence and tilted the screen away. ‘I’m OK mum. I’m not hacking into the Pentagon or anything like that.’ Michelle held her hands up in surrender. She scalded the pot and leant on the worktop while the tea steeped, thinking it wasn’t the right moment but she’d have to restrict Emma’s time, ask for the tablet to be left on the mantle where she could see it, or at least turned off late at night. It wasn’t as if she was a technophobe – Michelle had a mobile phone – but Emma said it was an embarrassment. It was one of those ‘ancient bricks’ Emma said with big, clunky numbers on it for ‘coffin dodgers with cataracts.’ Most of Michelle’s friends were always online, but she wasn’t interested. After a day staring at a computer screen at the call centre, the last thing she wanted to see was another keyboard.

‘You’ll be old one day,’ Michelle said, although she was only forty-one. Later, when the bells failed to ring, she saw the screen on the tablet would light up for a few seconds, so Emma must’ve silenced it. She texted Gary, something she hadn’t done for weeks. He told her to lighten up. All the kids are doing it and you would be too if you weren’t so old. He’d put a smiley face after that as if he hadn’t meant it. Gary’s latest model, Amber, was twenty-one.

Emma was running a hot bath so Michelle microwaved her tea – she hated waste – and went online. Michelle tried to concentrate, reading what other parents were saying and doing as she sipped her tea. She didn’t sleep that night and kept tossing and turning, wrapped up in the covers, when her phone vibrated on the bedside cabinet. She squinted at the green diodes on the alarm clock, bleary-eyed. It was a little past two. It was Gary and he’d been drinking – the only time he got to thinking – if you could call it that.

Any bother with fellas you know where to come

Michelle took a sip of water. Another message pinged from Gary. Something about ‘doing time’ if any fella laid a hand on his ‘little girl.’ She turned off her phone and padded across the landing to the toilet. Unusually for a teenager Emma slept with her bedroom door ajar. She hated the dark and settled for the soft amber shade of the landing light poking through the crack in the door. Michelle peeped around the door, watching Emma just the same as she had when she’d been in her cot. Still my baby, she thought. Emma was curled up foetal and the duvet had rucked up between her back and the wall. Michelle kicked off her slippers and crept across the soft shag pile carpet. She’d almost reached the chest of drawers when she froze as the tablet vibrated, its screen bathing the white ceiling in a rectangle of soft blue light. Michelle stood perfectly still, breathing through her nose, waiting for her pulse to settle and stop thumping in her neck. Emma shuffled under the covers and turned in towards the wall. Michelle was being stupid. It’d be some automated email, she told herself. She must’ve waited three or four minutes until she was sure Emma was sound and her breathing steady. She reached across the pile of clothes Emma had kicked off and took the tablet, holding it almost at arm’s length as if it was a bomb that might go off. She inched back across the landing and closed her bedroom door with a toe, listening to check Emma hadn’t moved. Michelle made a break in the curtains and sat down on the window ledge. It wasn’t quite a full moon, but you could see its milky reflection in the windows and windscreens along the avenue. She’d seen the message, a man’s name. It wasn’t a name she knew.

Are you awake?

She took a deep breath, muttered ‘sorry’ and swiped the screen to read.

Did Emma know she’d read her messages? Three nights had passed and Emma had hidden the tablet while she slept. It wasn’t in the bedside cabinet, wasn’t stuffed in the growing pile of laundry. Gary told her not to worry. She’s home, isn’t she? There hadn’t been much to read, after all. Whoever ‘Jack’ was he seemed to want to talk about music mostly, sometimes films.

Friday evening, a little before teatime, Michelle was stacking towels in the airing cupboard when Emma sidled past on her way to the bathroom. ‘Oh yes?’ she said.

‘I’m getting ready,’ Emma said and slammed the bathroom door, sliding the bolt across.

‘What are you getting ready for?’

Emma sighed, stepping into the shower. ‘I’m going out with Fee and Beck.’

‘You can have your tea first. We need to talk.’

Michelle was picking up socks and crumpled T-shirts when she saw the tablet on Emma’s jeans at the end of her bed. Michelle sat on the end of the bed, listening for the gush of the shower head, the creak of the copper pipes. She swiped the screen and began to read.

Gary told her to lock the doors and windows, said he was working local and he’d be round in twenty. ‘Blame me if you like. She’s going nowhere.’

‘She’s already gone.’

‘She’s done what?’

Michelle rubbed her forehead. ‘She’s not a little girl anymore, Gary. I couldn’t keep her here.’ He cut the connection. Ten minutes later he was hammering on the porch door. She’d changed the locks the day he’d walked out. He was in filthy mechanic’s overalls, with paint spattered down the shins. At least he hadn’t brought Amber. ‘Where the hell is she?’

‘She’s out with her friends.’

‘And you know that, do you?’

Michelle filled the kettle. ‘They called for her. She’s gone into town. She’ll be OK.’

Gary cracked his knuckles. ‘How do you know they’re not covering for her? How do you know she’s not with him, Shell?’

She slid his mug across the table, handed him the sugar. He still took three sugars, was still built like a streak of piss. She opened the kitchen drawer and took the tablet out from beneath the tea towels. ‘She hasn’t arranged anything. I’ve been reading their little chats.’

‘Does she know you’re doing that?’

‘No. Well I don’t think so.’

‘She’s got a password?’

‘She has to share it with me. That’s the rule. But she’d hardly be happy about me reading this, would she?’ She tapped the screen, entered the password and handed it to him. He scrolled up and down, his jaw clenched and she saw that familiar tic in his cheek. Gary shrugged. ‘He’s some dirty old man.’

‘But what if he’s her age? What if he’s just a lad?’

Gary shook his head. ‘Doesn’t feel right.’ Gary was typing. He held the tablet, frowned and deleted what he’d written before starting again. ‘That’s better. Look’

What R U doing?

They sipped their coffees. Gary said to wait. Michelle was washing up when the tablet vibrated.

‘It’s him. What did I tell you?’ Gary said.

‘What if he’s a mate, Gaz?’

Gary wasn’t listening. He typed away, grinning when replies came back. ‘Nine tonight,’ he said.

‘We shouldn’t be doing this, Gaz. She told the truth. She isn’t meeting him.’

Gary’s jaw clenched. ‘You seen what he’s been writing?’ He jabbed a finger at the screen. ‘Asking her if she’s got a bloke?’

‘Remember some of the stuff you wrote to me?’

‘That was different.’

‘How?’

‘She’s my girl. If he’s done nothing wrong, well he’s nothing to worry about, has he?’ Gary got up. ‘Catch you later, petal.’

‘Gaz, are you going after him?’

Gary gave her a wink. ‘That’s for me to know, sweets. You sit tight.’

Michelle climbed the stairs and watched Gary from a gap in the bedroom curtains. He was slinging stuff about in the back of his van. He slammed the back doors, didn’t bother to padlock them. He pulled a woolly hat down to his ears as he broke into a stride. A wrench gleamed in his right fist. What had she done?

Gary chose a spot behind the bandstand, clearing a space in the litter and dead leaves beneath a sprawling rhododendron bush. The Dingle was where he’d first met Michelle. He’d been drinking cider, couldn’t remember what he was doing there, maybe fishing. It was something her mates had fixed up. She was shy and unsure of him, the first girl who’d made him wait for a proper kiss.

The bench by the river was what he’d agreed with Jack. Now Gary was cursing himself realising there must have been ten benches by the river, stretching from the war memorial all the way to the weir. It was cool for summer and that suited him. He didn’t want folk poking around, didn’t want any witnesses. A couple of students were kissing, drumming their heels against the bandstand. An old fella was walking his terrier sniff and piss against every dandelion. Gary got to his feet when he spotted a bloke in tracksuit bottoms and a faded baseball cap hanging about under the bridge. Gary felt for the wrench in the leaves, gripping the cold metal and sliding it up his sleeve.

Gary walked along the river path, hands stuffed in his pockets and his head bowed. If this was Jack, he was no spotty teenager. Baseball cap had turned his back against the breeze to light up a fag. Smoke blew over his shoulder. He was waiting, alright. Gary jogged across the grass. Baseball cap took a deep draw as he turned. Gary let the wrench slip from his sleeve.

‘You’d be Jack,’ he said.

‘Yeah, that’s-’ Baseball cap’s eyes widened as Gary swung the wrench, socking him in the jaw. Metal cracked bone and he fell sideways, splashing headlong into the river. His cap drifted downstream, tangling in the reeds. ‘You leave my girl alone or you’re dead.’

Baseball cap floated face down, a trail of blood bubbling from his head into the muddy river water. Gary heard the shouts, but he didn’t react to them. He’d only meant to give him a scare but now Gary was panicking cos the bloke wasn’t coming up. Gary waded into the river and was waist deep when he was struck across the temple. He blacked out as he went under.

She’d left her tea untouched, wracked with worry. She was gathering the plates when the doorbell rang as she knew it would. She saw two of them through the frosted glass. They asked her to confirm her name. The taller one had a shaving rash on his neck, a speck of toilet roll dabbed to staunch a cut. ‘We need you to come to the station.’ The taller one took her by the elbow. They wouldn’t talk in the car but the taller one was driving and kept glancing back at her in the rear-view mirror. They were buzzed through a metal gate into custody and sat her down on a bench.

‘He’s here, isn’t he?’ she said. Neither of them answered. ‘I can see his bloody boots outside that cell door.’ A puddle of water had spread around the sopping leather. The custody sergeant set down his pen and beckoned her over. ‘He’s your fella, is he?’

Michelle frowned. ‘Not anymore.’

‘You understand why you’ve been arrested?’

Michelle nodded, but she couldn’t recall the words. ‘What’s he done?’

The sergeant said nothing but one of the younger officers spoke. ‘He’s just put one of ours in a coma. That’s what he’s bloody done.’

The sergeant told him to shut it. She had to sit down. She put her head between her legs as blood rushed through her ears. She heard something about fetching a glass of water. They put her in a room with a policewoman. ‘You don’t choose your men well, do you?’

‘He’s not my man.’

The policewoman couldn’t have been long out of college, but she pursed her lips and told Michelle what had happened. Jack was a young detective constable. It was a cop who’d written those messages. If Emma had turned up as he thought she would, he’d have marched her straight round to her parents and offered them advice, warned them of the dangers of grooming. It had happened to his sister and what he was doing wasn’t official police business. But he hadn’t met Emma. Instead he’d run into Gary. His skull was fractured and there was bleeding on his brain. They got the wrench from the river. Michelle said she was sorry, said they could take the bloody tablet.